AUTOCUE

DAINE SINGER GALLERY | MELBOURNE | OCTOBER 2011

‘THE ORSZÁG CODEX’ EXHIBITION ESSAY

BY DR ASHLEY CRAWFORD

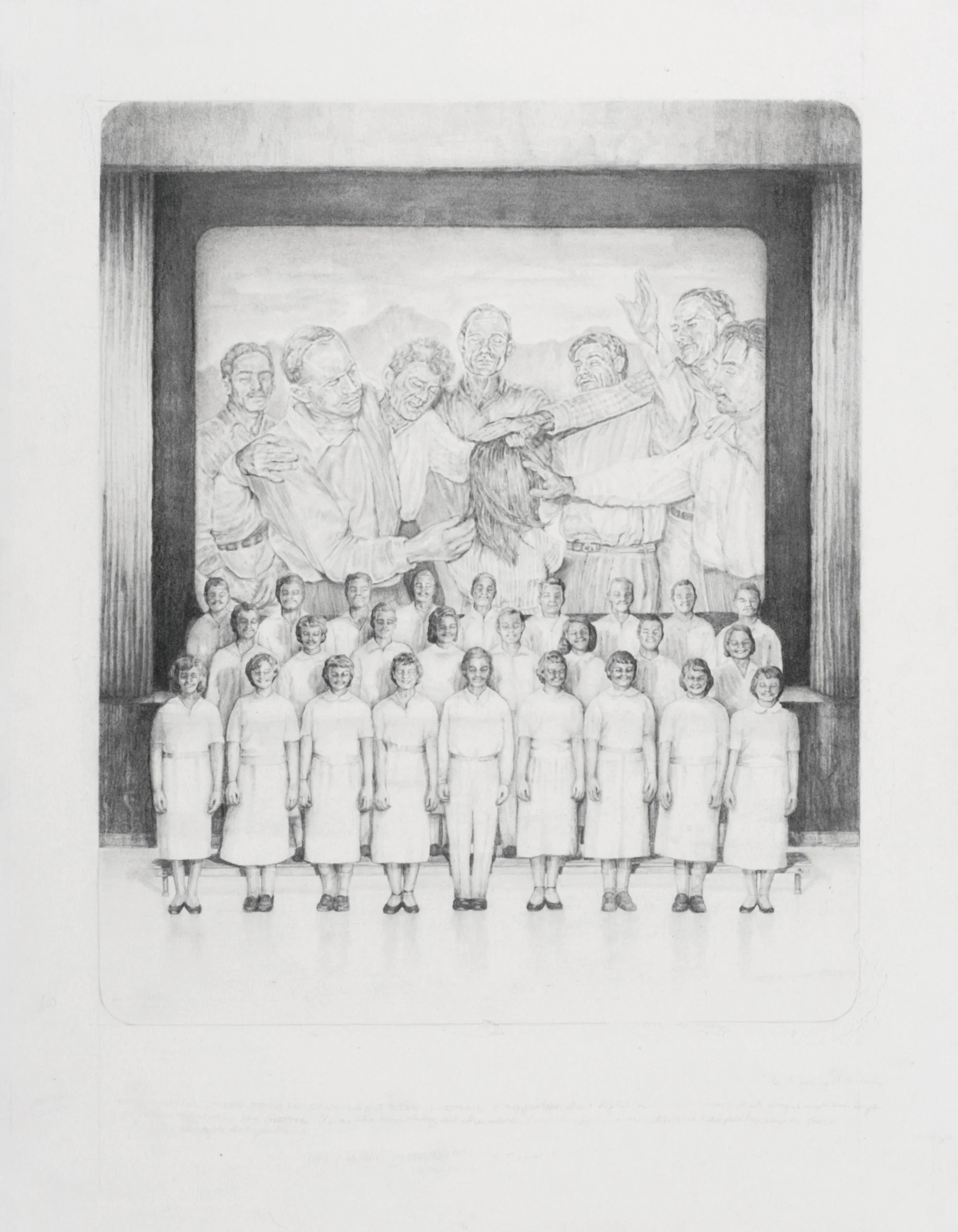

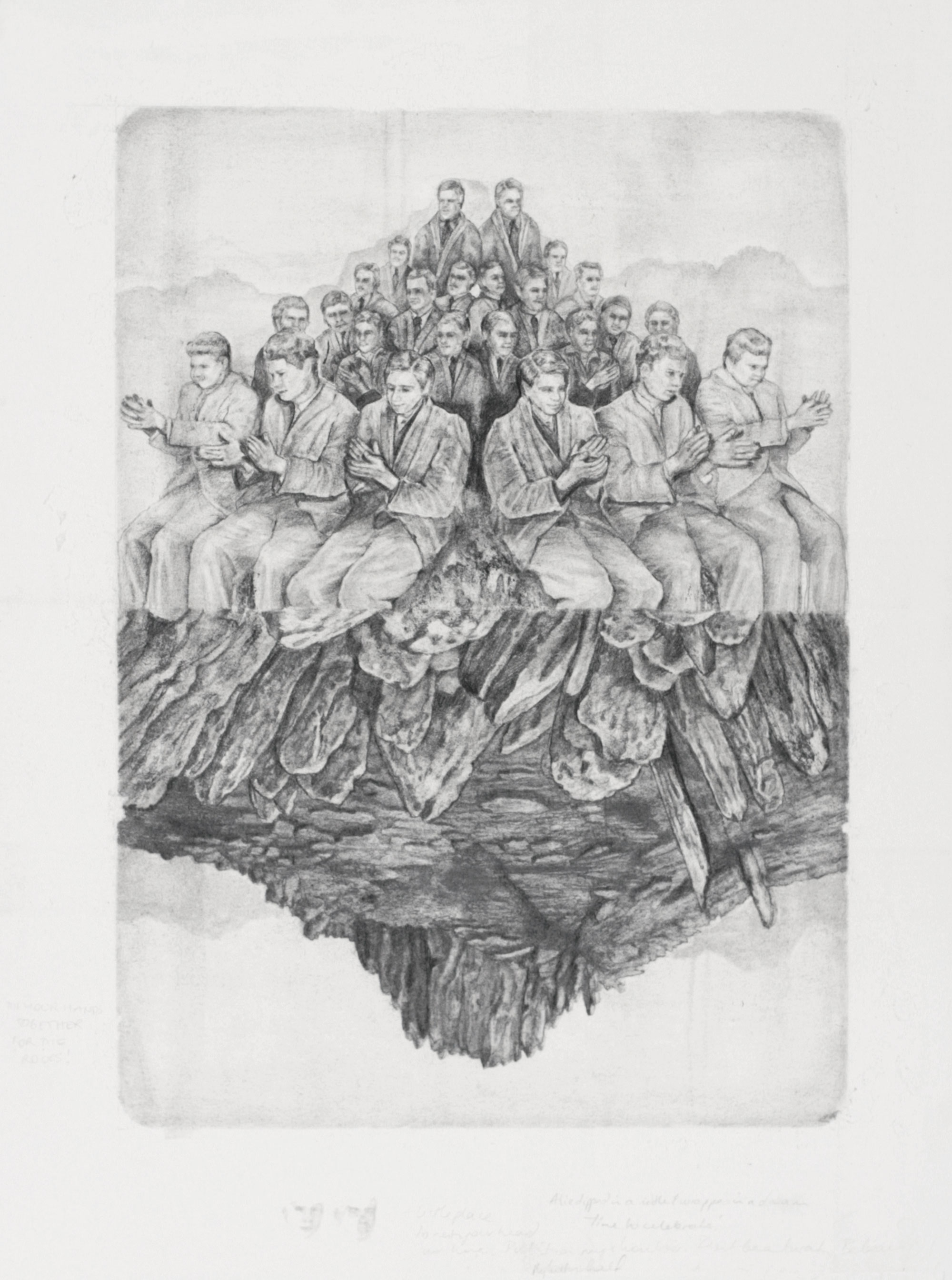

Over the centuries secret texts have been distributed by stealth, often more rumor than parchment, considered heretical, too radical for broad dissemination. As the centuries pass they become unbound, once cohesive chronicles separated by treasure hunters, framed as curios. From what scant evidence that we have at hand these pages come from an archaic exploration of both physical and philosophical intent. At times they are perhaps literal renderings of sites of power, at others they are clearly, or so we suppose, metaphysical musings on both the strength and frailty of humanity. The almost indecipherable notations and faded watermarks show the hand of a fine artisan. The works are illuminated in greys and blacks, finely and delicately rendered. Clearly great care has been taken to reveal a message that is now obscured by time. Many have wondered whether, as a cohesive whole, these pages contain the signposts of hidden treasure, although whether of a spiritual or fiscal nature remains unknown.

Becc Ország is the kind of artist that inspires arcane musings. Her works on paper, whether they feature human beings, landscapes or a bizarre combination of both, carry a strange timelessness and intensity. I have only seen her works in the flesh twice – once at the RMIT graduate show in 2010 and then in a group show at Dianne Tanzer Gallery in 2011 – and both times the images have lingered, seared onto my retina with a force that belies their humble stature as works on paper.

A part of this is, of course, simply skill. Ország, like her contemporaries Daniel Price and Jackson Slattery, is not afraid to show off her ability when it comes to carving graphite into paper. This return to draughtsman-ship and a sense of formality in execution, coming from such a young generation, is an odd twist in contemporary Australian art, as if they are conjuring a sense of nostalgia, resuscitating skills from decades past. This sense of mystery in Ország’s work is abetted by her pretty much indecipherable notations, jotted hastily as she works, hinting at a sense of utmost urgency. Are these in fact profound musings? Or are they miscellanea, the detritus of left-over thoughts? Do they in fact even relate to the imagery? That is a conundrum that Ország bequeaths to the viewer.

And for all the tightness of composition, these are by no means ‘clean’ works. Ország leaves the marks of mark making, the scratches and smudges, for all to see, thus contributing to the strange sense of urgency the works exude. These works hover between hints of the Surrealist impulse – imagine the notebooks of Hans Bellmer – with the grandeur of nature that has inspired such artists as David Caspar Friedrich. Ország’s work could well be pages from an aged codex, one that was once bound between illuminated covers of human bone, the artists’ own skull, but now let loose, page by page, to draw us into their depths.